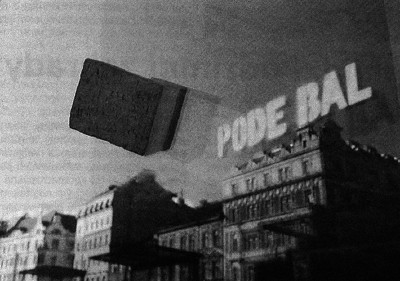

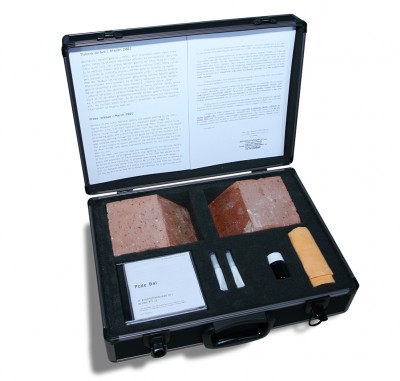

Institutionalized Art, 2002

Guerrilla installation, entrance of the Collection of Modern Art, National Gallery, Prague, February 2002

This guerrilla installation was a direct attack on the institution of the National Gallery, its politics of the time and especially its Director, Milan Knížák, who openly denounced any interest in the public’s view of “his” institution. A brick, split in two halves, was fixed onto the main front windowof the National Gallery in such a way as to create the illusion of it passing through the glass, half inside and half on the outside. One of the intentions was to force the institution to take legal action against Pode Bal. The National Gallery removed “its” half of the brick after a week. The outside “public” half remained attached to the window for over a year.

Press release

Visitors of the Czech National Gallery and people passing by its monumental museum of modern art (Veletržní palác) might for a moment think, that their eyes are deceiving them. There seems to be a brick flying through the glass window front. But then there is no sound of breaking glass and everything looks too still. The brick seems to be perpetually passing through the front glass barrier of the museum and it was installed there by Pode Bal, under the title „Institutionalized Art.“ The project reacts to recent politics of the National Gallery and its director Milan Knižák, who openly expresses contempt for any other opinion than his own.

Pode Bal says: „We want to urge the management of the National Gallery to restrain from its arrogance and to stop ignoring the opinions of the public and especially of the professionals in the field. We appeal to the directors of this institution to promote open dialog even with those, whose opinion may differ from that of Mr. Knížák. We’d like to remind all, that the National Gallery is a public institution, funded from tax income for the benefit of all and not a house of services for a self-invited elite.“

PODE BAL 2002

interview: Martina Pachmanová and Petr Motycka

A few weeks ago the group Pode Bal, whose member you are, introduced a “guerrilla“ project of its kind in the National Gallery in Prague. It is called Institutionalized Art. From the outside and inside of the facade of Veletržní palác you installed – without any previous notice – a halved brick which looks as if it were flying through the glass wall. It was a sort of non-violent metaphor of a violent penetration of an outside element into the institutionalized ground. What brought you to this intervention?

There were more reasons for this action but I would like to speak about the political and social level of Institutionalized Art – and that is the present program and function of the National Gallery and its tandem management of Knížák and Kolíbal. NG is a public service institution and therefore it should be accountable to the public – amateur and professional. The main impulse for the realization of our project was a public discussion about the position of contemporary art in the NG museums. This happened at the New York University in Prague in November last year. The general manager of the NG said twice in there, that he will not be accountable to anyone for his decisions and that the opinions of artists, curators, art-historians and journalists, present and absent, do not interest him. Our project was a reaction to this repeated demonstration of arrogance by Mr. Knížák.

A halved brick, glued to both sides of the glass facade naturally extenuates the border which exists between the inside and outside, between the elite space of a museum institution and public space of the street. Why this “interspace“?

The project was conceived as a metaphor of breaking through a barrier which makes the complexities and decision making of the NG from the outside completely untransparent. This barrier we wanted to breach symbolically. The NG approaches the “national cultural heritage” as a means of petrification of the present state of society and its priorities, instead of trying to discover new directions through art. Pode Bal considers activities of the NG today as parasitism on art in order to fulfill its own political goals. NG is not a friend of contemporary art but its normalizator. Moreover, through the installation, we also wanted to point to a more general problem of the self-centered institutional power which ignores public opinion.

Isn’t it quite absurd that you criticize an institution lead by an artist who, in the 60s and 70s, rebelled against the power structures by similarly alternative means?

It is absurd and we stress this fact. The brick which creates an illusion of flying through a facade was to remind Knížák

of his past and of how easily he had blunted the edge of his fluxus-time happenings and art. The manifest of Aktuál has surely a lot to do with the activities of Pode Bal. If the present situation persists we will keep reminding Mr. Knížák of his past on the facade of the Veletržní palác, again and again.

What was the reaction to Institutionalized Art?

I have only internal information from the NG because the general director, as well as the director of the Modern collection, decided not to react publicly to our action. As to the media, the interest and commentaries were not as big as we expected. But I’m still satisfied with the project because even if the reaction inside NG is covert, the created situation will have to be solved on certain levels, including the trivial question of how to remove a brick stuck to the glass with a special glue. The media feedback is always important in such interventions, the more because our goal was and is to stir up a discussion on this matter.

That is true but public art is very often realized anonymously, and its “merging“ with public space can be the best intervention and the most consistent resignation to institutional rules...

Yes, but our project is specifically about a public service institution and it needs a public dialogue. Pode Bal is against any form of artistic bootlicking of official structures, of course, and that is why we sometimes choose for of our projects illegal, non-approved ways. Art doesn’t always have to be something official – as Duchamp showed – it is a simple human activity, a natural intention to create. Art should react to the state of the society and to be valuable it should come out of an authentic milieu in which the artist lives. That is why we react to the antagonistic relationship of the NG to contemporary art which is seen in the number of the curators of the modern collection who left recently – willingly or not. Where this antagonism doesn’t count, is in the case of Milan Knížák. He doesn’t hesitate to buy his own art into the collections or – as we can see in the forthcoming exterior installation of the contemporary Czech sculpture in front of the Veletržní palác (Kolíbal, Nepraš, Veselý, Malich and Knížák) – to exhibit his own works wherever it’s possible. I don’t want to say that Mr. Knížák doesn’t have his place in the history of the Czech art of the 1960s and 1970s, but as the top representative of this institution he certainly cannot present himself!

The Pode Bal group “became famous“ thanks to uncompromising critique of many social, political and cultural problems. several years ago, in the foyer of the Parliament you exhibited a series of posters concerning the very controversial anti-drug law. That irritated many Czech legislators. In 2000 in the exhibition Malík Urvi in Špála Gallery you touched some very sensitive questions of diffusion of former Secret Police agents into the economic and political elite of this country; its result is well known: the Špála Gallery lost a rich, state owned sponsor. Now you are aiming at the cultural politics of a state art institution. Do you think that critically oriented contemporary art can have a specific influence on the events in the society?

Of course. To influence society is one of the functions of art. This aspect is, unfortunately, fairly neglected in our country. When we look around the world, art has currently a very strong tendency to speak uncompromisingly about various social, political and even economic questions. This could be seen at the last Biennial in Venice. Art which doesn’t hide from the complexities of the world has a good possibility to evoke some reaction in the society. And not only this. Political parties, big corporations or advertising agencies have many interesting strategies which artists can appropriate and turn against their originators. In other words, the artist who is not indifferent to what happens around him or her, can, from these strategies, gain a very useful tool for subverting the untouchable and power authorities of any kind. It is a way of appropriation of a certain model with the aim to disorganize this model from the inside. And Pode Bal is attempting something along those lines.

The so called engaged art is still considered by the Czech scene a relic of the past regime and is a priori linked with ideological propaganda. Pode Bal approaches this form of art without prejudice. Would you go as far as to describe your activities as political art?

A big part of our projects is political. But thinking of it, I would go as far as to describe any contemporary art as political – at least in a certain sense. I don’t mean the connection of art and activities of some political party or an explicit expression of a political content by visual means. More, I think of the inevitable political context from which contemporary art originates. But also art that evades this context and whose author deliberately tries to stay aside is political art. What gives such art work its political dimension is paradoxically its apoliticalness. The present day visual communication occurring in the public including art, advertising or political propaganda inevitably has a certain political status through its linkage with the ideological environment (which, of course, is the museum of art as well) and the market. To stand up against these bonds is a political act in itself.

I will give you the same question I used in my interview with Jiří Příhoda: Veletržní palác is a Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art and in front of the entrance of this huge building there is a big banner inviting people to see the art of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. However, the director of the National Gallery said many times that this institution is not a Kunsthalle and that he is not going to indulge in exhibiting or collecting contemporary art. How do artists of your generation understand this fact and what do you think of this?

I’d love to be wrong but I’m afraid that among Czech artists of any generation there is not enough engagement – not in the sense of conformity but in the sense of criticism. I spoke about this a while ago. I have a feeling that most artists don’t care. Instead of speaking publicly about similar problems they make their “apolitical” art in their studios. If the National Gallery claims to work with the art of present day, which means 21st century, they should do it, and not just preserve the so-called established values. Contemporary art is an extremely complicated organism and it is becoming more and more complex. If the National Gallery decides not to reflect this development it only furthers the already huge public ignorance and misunderstanding of contemporary art. It is a vicious circle. To destroy it we need many things but one of them is the engagement of the artists themselves. Otherwise we will have a National Gallery which dangerously resembles the tin can of Piero Manzoni whose content is well known to everybody: Merda d’artista.